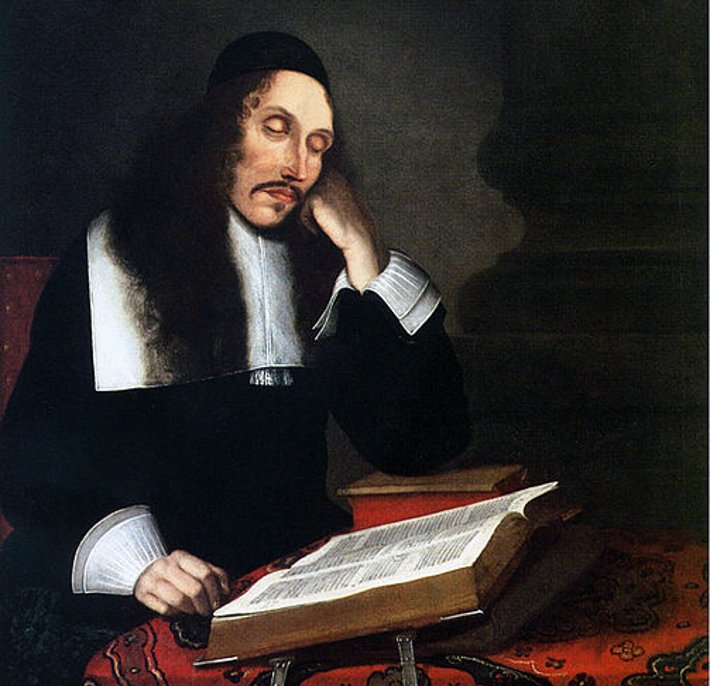

A selection from Tractatus de Intellectus Emendatione (Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect, or, On the Improvement of the Understanding) by Baruch (Benedict) Spinoza, 1657-60.

Conceived in the vein of Descartes Meditations (which was published some 20 years prior [see Foucault's Historie de la folie, chapter The Insane, where he relates Spinoza's project with Descartes meditative exercise]), and contemporary with Port-Royal Grammar and Pascals foundational work on the mathematics of probability, the Treatise, which comes down to us in an unfinished state, was probably written in the aftermath of Spinoza's excommunication from the Jewish community of Amsterdam (1656), although it remained unpublished until his death. The following notice to the reader was written by the editors of the Opera Postuma (posthumourous works) in 1677:

Conceived in the vein of Descartes Meditations (which was published some 20 years prior [see Foucault's Historie de la folie, chapter The Insane, where he relates Spinoza's project with Descartes meditative exercise]), and contemporary with Port-Royal Grammar and Pascals foundational work on the mathematics of probability, the Treatise, which comes down to us in an unfinished state, was probably written in the aftermath of Spinoza's excommunication from the Jewish community of Amsterdam (1656), although it remained unpublished until his death. The following notice to the reader was written by the editors of the Opera Postuma (posthumourous works) in 1677:

This Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect etc., which we give you here, kind reader, in its unfinished [that is, defective] state, was written by the author many years ago now. He always intended to finish it. But hindered by other occupations, and finally snatched away by death, he was unable to bring it to the desired conclusion. But since it contains many excellent and useful things, which - we have no doubt - will be of great benefit to anyone sincerely seeking the truth, we did not wish to deprive you of them. And so that you would be aware of, and find less difficult to excuse, the many things that are still obscure, rough, and unpolished, we wished to warn you of them. Farewell.

[1] (1) After experience had taught me that all the usual surroundings of social life are vain and futile; seeing that none of the objects of my fears contained in themselves anything either good or bad, except in so far as the mind is affected by them, I finally resolved to inquire whether there might be some real good having power to communicate itself, which would affect the mind singly, to the exclusion of all else: whether, in fact, there might be anything of which the discovery and attainment would enable me to enjoy continuous, supreme, and unending happiness.

[2] (1) I say "I finally resolved," for at first sight it seemed unwise willingly to lose hold on what was sure for the sake of something then uncertain. (2) I could see the benefits which are acquired through fame and riches, and that I should be obliged to abandon the quest of such objects, if I seriously devoted myself to the search for something different and new. (3) I perceived that if true happiness chanced to be placed in the former I should necessarily miss it; while if, on the other hand, it were not so placed, and I gave them my whole attention, I should equally fail.

[3] (1) I therefore debated whether it would not be possible to arrive at the new principle, or at any rate at a certainty concerning its existence, without changing the conduct and usual plan of my life; with this end in view I made many efforts, in vain. (2) For the ordinary surroundings of life which are esteemed by men (as their actions testify) to be the highest good, may be classed under the three heads - Riches, Fame, and the Pleasures of Sense: with these three the mind is so absorbed that it has little power to reflect on any different good.

[4] (1) By sensual pleasure the mind is enthralled to the extent of quiescence, as if the supreme good were actually attained, so that it is quite incapable of thinking of any other object; when such pleasure has been gratified it is followed by extreme melancholy, whereby the mind, though not enthralled, is disturbed and dulled. (2) The pursuit of honors and riches is likewise very absorbing, especially if such objects be sought simply for their own sake, [a] inasmuch as they are then supposed to constitute the highest good.

[5] (1) In the case of fame the mind is still more absorbed, for fame is conceived as always good for its own sake, and as the ultimate end to which all actions are directed. (2) Further, the attainment of riches and fame is not followed as in the case of sensual pleasures by repentance, but, the more we acquire, the greater is our delight, and, consequently, the more are we incited to increase both the one and the other; on the other hand, if our hopes happen to be frustrated we are plunged into the deepest sadness. (3) Fame has the further drawback that it compels its votaries to order their lives according to the opinions of their fellow-men, shunning what they usually shun, and seeking what they usually seek.

[6] (1) When I saw that all these ordinary objects of desire would be obstacles in the way of a search for something different and new - nay, that they were so opposed thereto, that either they or it would have to be abandoned, I was forced to inquire which would prove the most useful to me: for, as I say, I seemed to be willingly losing hold on a sure good for the sake of something uncertain. (2) However, after I had reflected on the matter, I came in the first place to the conclusion that by abandoning the ordinary objects of pursuit, and betaking myself to a new quest, I should be leaving a good, uncertain by reason of its own nature, as may be gathered from what has been said, for the sake of a good not uncertain in its nature (for I sought for a fixed good), but only in the possibility of its attainment.

[7] (1) Further reflection convinced me that if I could really get to the root of the matter I should be leaving certain evils for a certain good. (2) I thus perceived that I was in a state of great peril, and I compelled myself to seek with all my strength for a remedy, however uncertain it might be; as a sick man struggling with a deadly disease, when he sees that death will surely be upon him unless a remedy be found, is compelled to seek a remedy with all his strength, inasmuch as his whole hope lies therein. (3) All the objects pursued by the multitude not only bring no remedy that tends to preserve our being, but even act as hindrances, causing the death not seldom of those who possess them, [b] and always of those who are possessed by them.

[9] (1) All these evils seem to have arisen from the fact, that happiness or unhappiness is made wholly dependent on the quality of the object which we love. (2) When a thing is not loved, no quarrels will arise concerning it - no sadness be felt if it hatred, in short no disturbances of the mind. (3) All these arise from the love of what is perishable, such as the objects already mentioned.

[10] (1) But love towards a thing eternal and infinite feeds the mind wholly with joy, and is itself unmingled with any sadness, wherefore it is greatly to be desired and sought for with all our strength. (2) Yet it was not at random that I used the words, "If I could go to the root of the matter," for, though what I have urged was perfectly clear to my mind, I could not forthwith lay aside all love of riches, sensual enjoyment, and fame.

[2] (1) I say "I finally resolved," for at first sight it seemed unwise willingly to lose hold on what was sure for the sake of something then uncertain. (2) I could see the benefits which are acquired through fame and riches, and that I should be obliged to abandon the quest of such objects, if I seriously devoted myself to the search for something different and new. (3) I perceived that if true happiness chanced to be placed in the former I should necessarily miss it; while if, on the other hand, it were not so placed, and I gave them my whole attention, I should equally fail.

[3] (1) I therefore debated whether it would not be possible to arrive at the new principle, or at any rate at a certainty concerning its existence, without changing the conduct and usual plan of my life; with this end in view I made many efforts, in vain. (2) For the ordinary surroundings of life which are esteemed by men (as their actions testify) to be the highest good, may be classed under the three heads - Riches, Fame, and the Pleasures of Sense: with these three the mind is so absorbed that it has little power to reflect on any different good.

[4] (1) By sensual pleasure the mind is enthralled to the extent of quiescence, as if the supreme good were actually attained, so that it is quite incapable of thinking of any other object; when such pleasure has been gratified it is followed by extreme melancholy, whereby the mind, though not enthralled, is disturbed and dulled. (2) The pursuit of honors and riches is likewise very absorbing, especially if such objects be sought simply for their own sake, [a] inasmuch as they are then supposed to constitute the highest good.

[5] (1) In the case of fame the mind is still more absorbed, for fame is conceived as always good for its own sake, and as the ultimate end to which all actions are directed. (2) Further, the attainment of riches and fame is not followed as in the case of sensual pleasures by repentance, but, the more we acquire, the greater is our delight, and, consequently, the more are we incited to increase both the one and the other; on the other hand, if our hopes happen to be frustrated we are plunged into the deepest sadness. (3) Fame has the further drawback that it compels its votaries to order their lives according to the opinions of their fellow-men, shunning what they usually shun, and seeking what they usually seek.

[6] (1) When I saw that all these ordinary objects of desire would be obstacles in the way of a search for something different and new - nay, that they were so opposed thereto, that either they or it would have to be abandoned, I was forced to inquire which would prove the most useful to me: for, as I say, I seemed to be willingly losing hold on a sure good for the sake of something uncertain. (2) However, after I had reflected on the matter, I came in the first place to the conclusion that by abandoning the ordinary objects of pursuit, and betaking myself to a new quest, I should be leaving a good, uncertain by reason of its own nature, as may be gathered from what has been said, for the sake of a good not uncertain in its nature (for I sought for a fixed good), but only in the possibility of its attainment.

[7] (1) Further reflection convinced me that if I could really get to the root of the matter I should be leaving certain evils for a certain good. (2) I thus perceived that I was in a state of great peril, and I compelled myself to seek with all my strength for a remedy, however uncertain it might be; as a sick man struggling with a deadly disease, when he sees that death will surely be upon him unless a remedy be found, is compelled to seek a remedy with all his strength, inasmuch as his whole hope lies therein. (3) All the objects pursued by the multitude not only bring no remedy that tends to preserve our being, but even act as hindrances, causing the death not seldom of those who possess them, [b] and always of those who are possessed by them.

[9] (1) All these evils seem to have arisen from the fact, that happiness or unhappiness is made wholly dependent on the quality of the object which we love. (2) When a thing is not loved, no quarrels will arise concerning it - no sadness be felt if it hatred, in short no disturbances of the mind. (3) All these arise from the love of what is perishable, such as the objects already mentioned.

[10] (1) But love towards a thing eternal and infinite feeds the mind wholly with joy, and is itself unmingled with any sadness, wherefore it is greatly to be desired and sought for with all our strength. (2) Yet it was not at random that I used the words, "If I could go to the root of the matter," for, though what I have urged was perfectly clear to my mind, I could not forthwith lay aside all love of riches, sensual enjoyment, and fame.

[11] (1) One thing was evident, namely, that while my mind was employed with these thoughts it turned away from its former objects of desire, and seriously considered the search for a new principle; this state of things was a great comfort to me, for I perceived that the evils were not such as to resist all remedies. (2) Although these intervals were at first rare, and of very short duration, yet afterwards, as the true good became more and more discernible to me, they became more frequent and more lasting; especially after I had recognized that the acquisition of wealth, sensual pleasure, or fame, is only a hindrance, so long as they are sought as ends not as means; if they be sought as means, they will be under restraint, and, far from being hindrances, will further not a little the end for which they are sought... .